Blogging, as anything else, is a matter of tradeoffs. I’ve been working on an argument which I think is novel and interesting but which requires a significant amount of stage-setting. Because this blog is an attempt to share ideas in bite-size pieces (with the aid of a vast web of knowledge to which I freely link) I’ve had to abandon the hope of providing this argument—yet. Instead, I’m going to carry the argument out over a number of posts which will link to one another so that you might better orient yourself. In what follows, I’m going to offer a corrective to some sloppy—and very common—thinking about the idea of Freedom of the Will. This is important, because as ethicists have long understood, responsibility depends on freedom. Here goes.

Freedom of the Will: A Primer

For a long, long time, the common positions one can take on the question of the freedom of the will (I’ll be abbreviating free will and freedom of the will as FoW from here on) have been understood. The atomists of almost 2,500 years ago certainly conceived of the problem as we do and it isn’t unlikely that their precursors were in the same boat. With Socrates and Plato, the difficulty of maintaining both the infinity of the mental and the finitude of objecthood was already coming into focus as the philosophical problem par excellence.

What the atomists developed was a way of conceiving the myriad happenings at the molar level of chairs and tables as a perspectival illusion which results from a truly massive number of super-tiny indivisible units interacting according to a few, simple regularities. This view is familiar for the same reason that the name is familiar—scientists in recent history revived the term as they developed a similar model of causal reduction.

It is this recognition of the possibility of causal reduction, despite appearances, which sets up the FoW problem as we know it today. The argument hasn’t changed all that much.

Here it is:

- Assumption: I have FoW

- Assumption: Each and every molar event is really a collection of microscopic, atomic events which are governed by simple rules

- Assumption: All of my actions—moving my vocal cords around, tensing a muscle—are molar events

- By 2&3, each and every thing that I do is really a collection of microscopic, atomic events governed by simple rules

- Assumption: FoW consists in my being able to determine and govern my actions

- By 4&5, I do not have FoW

- By 1&6, I both have and do not have FoW. CONTRADICTION!

This is a standard reductio ad absurdam and it should be dealt with as such. If you are a FoW

proponent, you can deny 2, 3, or 5 (or some combination, but what we’re interested in is what kind of content is possible given assumption 1 and by keeping the claim-pool as large as we can, we maximize information about the space of possibilities in which FoW is possible).

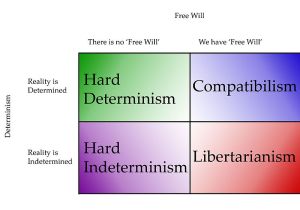

- Indeterminism: Denying 2 can be done by abandoning the view that atoms are governed by simple rules (this has been tempting to philosophers and laypersons alike who think quantum mechanics will provide some means of escape from the problem). What you’re left with is an indeterminist position in which one can hold that the causal claim fails universally (the aforementioned proponents of the QM solution do this) or that, somehow, cause and effect steer clear of minded beings like us.

- Libertarianism: Denying 3 is simply denying that my actions are truly molar events. More precisely, the position holds that my actions are something altogether different. By the beginning of the renaissance positions that denied 3 were becoming rather ugly: the self and the will, no longer claiming sovereignty over the whole domain of the body (because of the growth of anatomy, the bizarre physicalism of Hobbes, and the soulful Cartesian philosophy), curled inward and eventually was relegated to the job of res cogitans; literally, ‘thinking thing’. In the wake of Newton’s Principia and the growth of a mechanics which was not only expressively more powerful than Aristotle’s physics but which, in addition, multiplied the effectiveness of society as a whole by expanding its predictive powers, this position became unpalatable to most thinkers. This is still the case, though I suspect that those who worry about qualia are, at least, flirting with this impotent school of thought. Despite its lack of popularity in the academy, it might be the most common folk view on the matter.

- Compatibilism: Denying 5 is tricky, but its rewards are great: completed successfully, our theoretical toolbox would include both the possibility of complete (insofar as physically possible) predictive power and an exalted, morally responsible view of the self. To be successful in this task, it isn’t so much that one must deny that FoW consists in the governance of one’s own actions (such a solution is possible only at the cost of all intuitive appeal) as that this governance must somehow be shown to be conceptually separable from the kind of governance that causal rules have over matter. Medieval philosophers, discussing this means of resolving a reductio said something to the effect of, “where there is a contradiction, introduce a distinction.”

Things Aren’t So Simple

Earlier, I said that denial of 2—that events are guided by regularities—was a means of keeping our assumption of FoW afloat. From the perspective of the reductio that we were looking at this is true. But reflection on the matter complicates things: there may be independent reasons to doubt that the lack of determinism in a physical system will yield FoW. If the deterministic control of an atomic physics can’t save us from the problem, neither can its opposite view: that the units which make us up are jumping around probabilistically or in an indeterminate manner. If being guided along a straight path by the arrow of time isn’t freedom, what more freedom is there in each moment’s event being the outcome of random, microscopic perturbations? The steady hand of a deterministic atomic theory is no more—or less—harmful than the palsied jitters of an indeterminate microstructure.

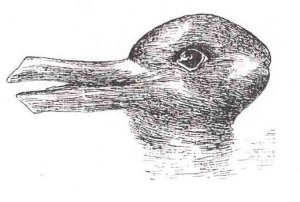

Something very peculiar is going on here. With the first argument, it was taken for granted that the determinacy of a system somehow precluded that system’s being free—that’s the motivation behind the sixth step in the argument—but later we saw that determinacy is no worse than its opposite as far as FoW goes. When one property, which is generally supposed to rely on another in some fashion (as the lack of FoW was thought to be a straightforward outcome of atomic determinacy), is invariant with respect to another, as FoW seems to be to the property of determinacy or lack thereof at the atomic level, you’re prima facie warranted in exploring the possibility that the distinctions that these properties cleave in the world-body are orthogonal.

Supposing that these distinctions carve at different joints, the next step should be to specify what FoW is if not the ability to guide one’s own actions in the sense that the laws of physics guide (better: articulate) the goings on at the atomic level. Now, there’s no such thing as ‘proper philosophical method’ (that’s an oversimplification—there’s no universally agreed upon method and, in fact, the search for method is a part of the philosophical enterprise), but as far as ‘best practices’ go, you can’t do much better than looking to actual cases in which a term is applied and attempting to say what it is that people are doing in so applying it. I want to be clear: philosophy is not a mere lexicographic or anthropological recording of regularities and it’s always possible that everyone is wrong about some question, but figuring out what people have meant by a term is one of the most powerful tools of the philosopher. For this method of analysis, the answer we seek is something that we have always already had.

In the parenthetical of the first sentence in the last paragraph, there’s just the kind of clue which will prove valuable for our discussion. What is the difference between the rules that I follow as a chess player—written down on a sheet of rules—and the rules that a collection of matter follows—written down in a physics text? What I’d like to suggest is that atoms simply act as they act and that we, at best, accurately articulate their doings while what humans freely do depends on some conception of appropriateness of doing. We can give reasons for an atom’s having done what it did, but there’s a richer sense of the term ‘reason’ which applies to the type of thing by which we can choose to do something.

My conjecture—and the moral of the story today—is that freedom of the will is a matter of choosing to act on the basis of reasons and that this is a feature that doesn’t depend on the features of the things of which we are constructed any more than the game of chess depends on the means by which pieces are moved around on the board. There is not some new, exciting scientific discovery which will show freedom to be a sham because freedom is a way of characterizing the relation between an actor and the reasons which that actor holds before her mind’s eye. Freedom is a notion that is internally related to the idea of the self. So, while one can abandon free will, one can’t hold that there exist selves that somehow lack it—freedom is a transcendental condition for the very possibility of having a self.

In a future post, I’m going to extend this argument and attempt to show you how freedom is something that can be created within a society and is not simply the type of thing that one always already has. The controversial thesis that will be approached at a later date is that metaphysical FoW is a regulative standard which should guide (and be tempered by, through dialog with) the political ideal of freedom. In preparation for that argument, feel free to skim my first post so that your mind isn’t polluted with the notion that there is some ahistorical perfected ideal of freedom which can be grasped without considering the institutions and networks of interaction in which people actually live and can be said to be free.

From blogroll inductee UnwelcomePundit:

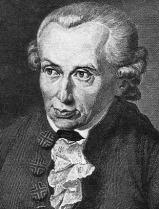

“Under these circumstances, the preferred player 1 choice is clearly not to lie; telling the truth is always preferred to lying. In such a situation, a game theorist will try to counter, saying that the above argument demonstrates a misunderstanding of the notion of utility. The payoffs above don’t represent monetary payoffs, they represent real payoffs in the form of a partial ordering of possible outcomes. If you think that cooperating is a good thing, then that will be a component of your payoff for cooperating. To put it more generally, whatever reasons you could possibly have for acting one way or another will be accounted for by your payoffs. So, if you like cooperating so much that it tips the direction of the above-mentioned inequalities, then you were never really facing a prisoner’s dilemma in the first place. What we would need to do to put you in that situation is to provide enough extra incentives to make defecting again seem like a dominant strategy. The game theorist’s presumption, moreover, is that such a thing can always be done.

“In player Kant’s case, however, piling on extra incentives will just never be enough. Even taking a and b down to negative infinity won’t work, because to Kant, c and d are already there. Moreover, adding an infinite number of incentives to c and d will not be enough to draw them from the abyss in which they began.”

via The Man Who Kant Lie.

The Use of Technology

Perhaps more difficult (but no less inevitable) than the creation of a technology is the task of coping with it once it arrives. The adjustments we make range from changes in conceptions of manner and politeness to revisions of the political contract; as the body of technology grows it must throw off the normative frameworks which are no longer capable of containing it. The body politic must undergo a process of moulting.

Consider the shit-show that is our national dialog on the second amendment: Are you an originalist about the second amendment? If so are you a reference-originalist (all and only breach-loading muskets and cannons available to those alive during the writing of the constitution are what it protects) or a sense-originalist (read: tanks, missiles, nukes and all modern analogs of the arms available at the time of the signing)? If not, what is your position but the ad hoc attempt to slow the progress of an inevitably fatal wound?

(I am told that there exist alternatives to originalism, though it is unclear to me how such alternatives could be cashed out–either of the positions I’ve sketched are attempts to understand the meaning of a piece of text as it was written. If you have a reasonable alternative in mind, I encourage you to explain it.)

The Problem: Characterized

The hermeneutic intractability of certain people’s positions on the second amendment notwithstanding, the purpose of this post is to highlight a trajectory towards a possible dystopian future. The problem, minimally conceived, is this: as our ability to engineer solutions to the ailments that evolution overlooked (better: never cared to look at) increases, and we move from patching up a failing system to outfitting it with potential upgrades, the laws that dictate a hospital’s legal requirement to stabilize anyone requiring emergency care won’t be strong enough to protect against the exacerbation of social inequality and the general bifurcation of outcomes for haves and have-nots.

More on this later. First, we have to understand the limitations of the social glue we inherited.

The Origins of the Problem

At one time, the arguments for private property didn’t extend beyond that which a claimant could personally use. As ‘personally use’ became a term so broad as to be meaningless (“Don’t I personally use Trump Tower? Look: my name’s on the damned thing!”) or as people stopped caring about the fine print of the arguments which provided apologia for their actions (assuming that they ever did), the billions upon billions of dollars amassed by figures such as Bill Gates became framework orienting examples of private ownership. At this point, it is commonplace to treat as equivalent 1) what a person has gathered together in a legal manner and 2) what a person has a right to claim as their own personal property. It isn’t uncommon to not even recognize that these two things are theoretically separable; yet they are not, as far as I can tell, analytically bound.

Why, then, is power not entirely pooled in the hands of a few? Shouldn’t we expect, if money begets money, that complete monopolization of power is a logical conclusion of capital? One reason is that humans are finite beings, only capable of realizing the grand schemes of reason within a limited scope and against the stubbornness of a material reality: we’re big, mammalian sacks of meat that lumber around and eventually collapse from wear and tear, at which point the identity upon which such things as property rights depend is scrambled in a great entropic orgy. We go to sleep and never wake back up to claim what is ours. Power is diluted as those who have it die off. It then pools up again as new humans accumulate wealth throughout their lives. (Now, of course, there exist political elements that are dead-set on eliminating the basically good and redistributive effects of death–but that’s another story.)

The Problem: Restated

As medical technology improves, we move closer to a point at which we not only sustain the mortal condition but augment it and practically move beyond it. If you have earned everything that you own and you can afford the unnecessary procedures which allow you to continue to expand not only the amount of money that you possess but the rate at which you acquire it, the idea of capitalism which is only imperfectly manifested by our fleshy embodiment could very well enter a stage of as-yet unfathomed inequality. Just as the syntactic engine’s asymptotic approach of a semantic engine yields something indistinguishable from the semantic engine—a mind—it seems that our tinkering with medicine might allow for a frictionless capitalism which is measured not in dollars but in hours.

Of course, I kind of doubt that people will throw off the yoke of fate entirely and begin ending lives prematurely (as they do in the movie I just referenced). But that’s not really necessary; all that this awful future requires is a supremely stacked set of dice.

The Problem: Generalized

Hopefully you see that there’s something very wrong here and potentially very dangerous. There are two morals that I think we can draw here, of which at least the first is useful to those uninterested in philosophical speculation:

1) A certain conception of human freedom is not the be-all and end-all of human flourishing: if unconstrained freedom leads to a possible future in which the term takes on an uncomfortably Orwellian shape, perhaps freedom (like all the rest of our great ideals) is not the type of thing that exists outside of careful meditations on the limits which we must impose on exercises of power. Understanding isn’t something you have it is something you can do through sustained dialogical effort.

The libertarian’s great flaw is historical blindness and the lack of imagination that comes with it.

2) Bioethics does not end at the body because the body does not end at the body: it is a tool whose location in social space can’t be exhaustively accounted for in three dimensions.